ARTS & COLLECTIBLES

VERMEER

AND

DE HOOCH

THE DYNAMIC DUO OF DELFT

EDITORIAL TEAM

Gemaldegalerie Berlin

Philadelphia Museum of Art

One of the great mysteries of the Dutch Golden Age is the relationship between Johannes Vermeer (1632- 1675) and Pieter de Hooch (1629-after 1686); They elevated Dutch genre painting to one of the most beloved expressions of the Golden Age and of the history of art. They are the Van Gogh/Gauguin, the Michelangelo/ Leonardo dynamic duo of Delft. There is not a single written document that shows an interaction between them other than their signatures one name apart on the St. Luke’s Guild of Art registry - but their pictures portray a unique dialogue and symbiosis in the history of Western art.

Both painters grew together innovating genre painting each often using their own family as subject in controlled settings. This was the Age of the Seen, when the microscope and telescope showed us the stars and sperm, and the camera obscura bridged the gap between sight and painting with spectacular images projected on a flat surface. Painting now had a new purpose: recording and honoring this new life seen by our expanding senses.

They were both fascinated with light. Vermeer was interested in contemporary optics and the way images were created and projected thru lenses (via the camera obscura). He usually portrayed a beautiful journey of light traveling from the upper left side of the canvas to the lower right. De Hooch studied light’s behavior on walls and materials, bouncing off surfaces at different angles and filtering thru glass and curtains. He painted dark rooms overlaid on light backgrounds with light filtering in through doors and windows, contre-jour (French: against the daylight). Vermeer painted his light effects with the mastery of soft and hard edges, of glazing and scumbling, of perfect shape and highlight while De Hooch's brushstroke traced the scene with a rustic poetry and caress. Vermeer’s work embodied eloquence, simplicity, detail, and concentration while De Hooch’s oeuvre has a homemade authenticity, a greater variety of elements and a more ambitious harmonization of complexity. It would appear that De Hooch initially inspired Vermeer's focus on juxtaposing geometry and the figure while Vermeer pushed De Hooch towards more refinement.

Both artists used their own surroundings and family as the subjects of their work. Vermeer painted his wife and children often as solitary figures absorbed in thought. They focused on simple daily activities set against the interior geometry, often overlaid with religious metaphor. Against the more Calvinist setting of the Dutch Republic, Vermeer converted to Catholicism to marry his wife and primary painting subject, Catharina Bolnes. De Hooch portrayed a more humanistic world, depicting the harmony of human relationships within his geometric interiors, also using his wife, children and friends. Sometimes their presences emanated outward towards us filling the space; sometimes they were confined to within, similar to Vermeer.

This was the Age of the Seen and to bridge the gap between pictorial representation and the actual world, artists in the 17th century often depicted curtains and frames as a middle step between outside and inside. Avoiding this device most of the time, PDH and subsequently Vermeer adopted the repeating rectangle idea into their pictorial worlds, a picture in a picture, echoing the outside boundaries of the canvas in a more eloquent way; a harmonious interface of real and painted edge.

Geometry was metaphor in painting. In the previous centuries, its idealized forms were associated with the religious via the cross or church interior, juxtaposed with the organic twisted or scurrying figures therein. In the emancipated Golden Age, however, geometry was transformed into the edges of the Dutch home, while still retaining a symbolic component. De Hooch used his rectangular doorkijkjes (Dutch for “through doorway views”) to suggest other dimensions for his figures and Vermeer used his rectangular maps. Much of each artist’s work deals with the relationship of the figure and this simple rectangle. Painting a painting or map in a picture is its own doorkijkje, and figures in painted doorways are also paintings within paintings. Maps were also (flat)metaphors for realms beyond the small corners of rooms where they hung. Mapmaking exploded in the 17th century Holland thanks to countless ship voyages exploring the old and New Worlds and were also symbolic of the Dutch command of world trade.

*Amsterdam and Delft btw was only a few hour horseback ride away.

Both depicted their Dutch home settings in series of pictures with similar compositional interests making them easier to group and compare. There are many examples throughout the career of both artists of one quoting the other (and many pictures were cross-attributed through the centuries) but while it was thought that Vermeer was the innovator, more evidence suggests that it was De Hooch who was often quoted by Vermeer. Pieter de Hooch was the master composer as evidenced in more than 150 surviving attributed works, full of complexities-while Vermeer’s extant oeuvre is 34 and generally similar in composition. Still, Vermeer was the consummate master of technique, of hard and soft edges, sfumato, simplicity of composition, separation clean sparkling light as experienced thru the novel optical devices developed at that time. Pieter de Hooch was the son of a bricklayer, piecing together vast compositions block by block, perhaps a little rustically but creating a special poetry out of a cacophony of pictorial elements.

There is a mutual respect and admiration that is apparent in both artist’s works through the Delft years and even after De Hooch moved to Amsterdam. The pictures are the evidence that the two artists must have stayed in touch (or at least seen each other’s work).* Let’s study individual pairs and try to understand why(until only recently with new scholarship) both artist’s works were often confused with the other.

The Women with a Child and her Maid and The Procuress 1656

Gemaldegalerie Berlin

Philadelphia Museum of Art

*we can date this fairly accurately after the birth of his first child Pieter in early 1655

Perhaps the earliest example of who led the charge into “geometric genre painting” is a comparison between PDH’s canvas of 1655-6* to Vermeer’s 1656 dated picture of the Procuress. Here we see De Hooch’s mastery of combining the interior architecture and the figure, of the appearance of his doorkijkje which will appear in almost every subsequent work while Vermeer shows his talent for rendering texture and color and organic composition but shows little of the geometric structures he would soon embrace. Both artists exhibit their interests in organization and rhythmic interplay of limbs and the figures. Vermeer divides his canvas in half horizontally between figures and drapery while De Hooch fractally repeats the canvas boundaries in squares and rectangles within, Mondrian-like.

Both would take notice of each other’s work and would evolve on a similar trajectory

The Card Players and Officer with Laughing Woman

These are the earliest more well know pendant PD/JV works. The brilliance and complexity of each artist’s canvas makes whoever came first almost irrelevant. Yet the De Hooch shows an earlier touch in his respective development than Vermeer and very likely predates it. But Officer with a Laughing Woman at the Frick Collection was one the author’s favorite paintings growing up as a young artist. The color and tone are extraordinary and the picture sparkles.

In the De Hooch, we have two figures at a table playing cards with one raising his arm poised to win the game with an ace. A maid in the back is stuffing a pipe and probably serves the group from the wine jug next to her. The dating around 1659 is supported by several factors: his color palette using red highlights and yellows, the objects including the jug, chair and painting that repeat in the dated 1658 Young Woman Drinking with Two Soldiers at the Louvre. It is likely that this scene takes place in the same room as the latter and several other canvases of PDH, likely upon his move to the Oude Delft from the Binnenwatersloot.

Gemaldegalerie Berlin

Philadelphia Museum of Art

De Hooch has the scene dynamic and handmade with arms flying and an attendant servant and uses stunning color arrangement with yellows, blacks and greens, purples with rich crimson accents. The Vermeer on the other hand, carves the scene in gemstone. The figures are immobile, but shining. There is an overall saturation of beautiful colors, creating a Dutch light that sparkles on the figures and echoes in the blues and warms of the map behind them.

De Hooch merges the foreground male figure’s hat with the dark closed window, moving that figure into the scene with the others while Vermeer exaggerated the contrasting presence of the dark male figure and hat against the bright window, creating an imposing presence out of proportion with the smaller female figure in the distance. The map on the wall that comes down and echoes the potent space between the man and maiden suggests he is worldly and possibly a traveler to the distant lands that the Dutch explored and traded at that time. And as Jonathan Janson states in his comprehensive website, Essential Vermeer, the beaver hat may refer to the exploration in the New World where beaver were eagerly sought out after having had been eradicated in most of the Europe.

Map making exploded in the 17th Holland and was its own form of representation of the world and was analogous to painting in a way. Vermeer frequently used maps to imply distance and a separate dimension from the main scene in the canvas as PDH did with his doorways.

Sometimes De Hooch comparisons don’t help. Vermeer’s Soldier with the Laughing Girl has been dated around 1657- no doubt to match up with the De Hooch although this canvas is too developed for Vermeer’s early period and is closer to other scenes in the 1660s using the same figure(his wife) and attire such as the Music Lesson and Young Woman with a Water Pitcher.

A more contemporaneous juxtaposition of works are these early pictures on tiled floors. Here we see one of Vermeer’s first depictions of a chair, used as a prop and catching the angled light thru the window. PDH uses a chair to repeat the flat geometry of the window frame.

Gemaldegalerie Berlin

National Gallery, London

Louvre

Courtyard

Gemaldegalerie Berlin

National Gallery, London

Louvre

We can see here similarities between Vermeer’s only outdoor works dated around 1660 and De Hooch’s famous courtyard scenes, a genre that he is credited to creating. In his NGA canvas, we see base of brickwork on the bottom quarter of the canvas with a sloping staggered composition from upper right to lower left. Vermeer simulates this but on a different scale in his Little Street and uses his own doorkijkje views that echo PDH’s London canvas. PDH has the element of movement in both pictures using the doorkijkje as a sort of time machine of coming and going while Vermeer uses them more as still ornamental vignettes. It is noteworthy however that JV’s two outdoor views are the only pictures he made that can stand alone without the figures. It is possible he replicated also PDH’s approach of creating the setting first in these works and adding figures later, unlike in the rest of his work.

Rothchild Collection

Mauritshuis

Both artists also created their own definitive Delft landscapes around this time. This is their “I am here” expose, their pride in being Delftians.

View of Delft is considered one of the great paintings in the world and shows Vermeer’s perfected technique of layering transparent and opaque dots and dashes of paint in an almost digital replication of light and form. He created an iconic image of the town; a sparkling sunlit Dutch Xanadu with passing dark clouds, now a metaphor of Delft’s brief glory set between two wars.

Its counterpart would be Pieter de Hooch’s Woman in a Bleaching Fieldprobably his best outdoor cityscape view. This was exhibited spectacularly in De Hooch’s Prisenhof exhibit in 2018. Which picture came first? Both pictures seem to play off of each other to some degree. Each shows local residents against the greatest hits of architecture in Delft as a backdrop. PDH zoomed in on the figures and their activities and managed to add a doorkjije while JV made a true cityscape, depicting the overall view with humans as antlike inhabitants in the scene.

This was likely the 3rd time PDH painted this view in extant pictures. It also shows his traditional manipulation of landscape elements at will; moving the Nieuwe Kerk to just behind the Oude Kerk and his garden building to the left of the scene. There is no actual point where all these edifices would line up in this same way. It appears that PDH painted the Nieuwe Kerk from life in the NGA/DC picture in 1657- 59 before any additions were added on the roof. This little sliver of plein aire painting with its sparkling color and realism may have impressed Vermeer.

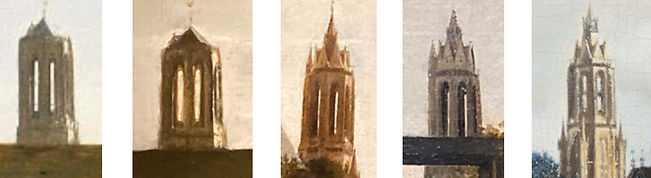

Vermeer’s version clearly is the same as PDH’s towers in the Rothchild canvas and the Family Portrait.

It appears PDH basically painted two versions of the tower in different years and replicated them each time for other canvases. This is surmised due to the second version’s lack of freshness and exact replication to the first. The second pair is also painted slightly east on the Oude Delft due to change in perspective in the carillon openings, but all versions reflect views that proceed the bell installation in April 1660.

Texas State University astronomer and physics professors published a study in Sky & Telescope Magazine in 2020 on when View of Delft was observed. They used Google Earth imaging and maps to confirm that the scene was accurately portrayed and then focused on the Nieuwe Kerk tower on a small sliver of light just grazing the central column and illuminating the left one. They also studied the clock and realized that it had been misinterpreted and actually read 8 AM. The belfry had no bells and so they concluded also that this was viewed before the bells were added in April 1660. They loaded up all this info in a computer and concluded that this painting likely reflected the view seen on Sept 3-4 1659 at 8 AM in the morning. This may just be the starting date as Vermeer worked meticulously and it is possible it was finished well into 1660 or even 1661.

There is a dialogue between these outdoor pieces but which came first? Due to Vermeer’s working methods and De Hooch’s expediency and move to Amsterdam in 1660-61, the bets are on De Hooch. One can imagine however that each artist visited each other’s studios while pictures were in progress. However, Vermeer was likely not working on this canvas in his town square location just a few blocks from PDH but rather in a makeshift studio where the view was seen itself on the edge of town about a 15 minute walk eastward.

Interiors 1660s

PDH approached interiors differently than Vermeer. Although his work is essentially about human activity and relationships in an interior, his settings are practically complete paintings in themselves. Take the figure out of a Vermeer however and the picture has a gaping hole and falls apart. His settings are created around the figure while PDH, son of the bricklayer, builds autonomous places where humans can come and go.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

National Gallery, Lond

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

Rijksmuseum

What we have admired in Vermeer’s art has often been the simple story of a female head and a rectangle behind her. Whether underneath, bordering, touching, overlapping, the big compositional drama seems to be this relationship between head and map. When the head is outside, it is framed against a white wall. When it is touching, it is marriage of ideas of brain and diagram, when the head overlaps the map, it is plunged into its virtual space and overwhelmed. These are the great narrative dramas of his heads. Of course, there is tonality, color and shape and a supreme elegance. But the stark modern Vermeer we know is much more the Pieter de Hooch Vermeer than we knew, interested in the harmonies between figure and geometry, between the painted geometry and the real shape and edge of the canvas. The map was the great craft of 17th century Holland, assisted by their mastery of the seas and far travel and commercial exchange, and an engraving tradition which began in Antwerp a century before. Maps are metaphors for the world, of vast space, of being somewhere else. They are a metaphor for painting itself, a flat surface with vastness within, a charting and journey for the eyes. A map within a picture was then a double metaphor.

If we compare this 1664 dated PDH picture with this Vermeer often placed around that time, we see both artists dividing the canvas into quarters and using the tension from the corner of map or window against the head. This creates a psychological tension of the human and geometry

Budapest Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

This solitary figure is very unusual for De Hooch (and repeated most famously in the pendants of both artists of women holding balances). It may have been a commentary on the losses of one of his children, Fransois and his mother-in-law, Diewerte who had recently died and left the house palpably empty. The bubonic plague hit the Netherlands again in the mid 1660s and wiped out 10%(24,000) of the population of Amsterdam.

Both artists also used undoubtedly their wives and children as models. This was the foundation of Dutch genre painting-depicting one’s own everyday life.

Vermeer apparently seemed to switch painting each of two of his children towards the end of his life. The famous girl with a pearl earring may be his daughter Maria who married the son of a prosperous merchant in 1674 after her father died. The other daughter, possibly Elisabeth, who was less attractive and had features that resemble someone with Down’s syndrome got equal time in his canvases. He appeared to paint one and then the other and then occasionally both together for the final third of his extant work.

More than Pieter’s household, Vermeer’s wife, who was a practicing Catholic, had children almost every year of their marriage. His household must have been filled with a continuous din of children crying, playing and some, unfortunately, dying. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, Vermeer sought the solitude of his upstairs studio where he could escape from the throngs of his offspring and paint the simple quietude of women absorbed in their daily tasks, undisturbed. Vermeer in fact depicted young children only twice in his work-his two landscapes - and they acted as small minor details in the broader composition. PDH had a more manageable population in his household and perhaps it was easier for him to focus on the relationships between mother and child.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mauritshuis

National Gallery, London

Kenwood, London

Woman at the Virginals

These two pictures appear to be almost mirror images of the same pictorial ideas: a flat white wall illuminated from the upper left filled with rectangles within rectangles. The foreground is set with a child in the De Hooch with its counterpoint of a chair against the wall, while Vermeer uses the empty chair- perhaps a metaphor of our own presence witnessing the scene- in the foreground. The open doorkjikje in the PDH perhaps finds its parallel in the open virginal. Even after De Hooch moved to Amsterdam, it is clear by these pictures from the late 1660’s, early 1670’s that each artist was aware of the work of the other.

National Gallery, London

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

Woman Holding a Balance

These are the most famous pair of rhyming PDH/JV works. Both canvases show a single figure, likely both artist’s wives, with similar dress at a table by a window with a rug draped over the left side. But then the pictures diverge: Vermeer uses a painting on the wall as his rectangle in rectangle device, while PDH adds his doorkijkje. Vermeer adds a mirror in the foreground with dramatic light filtering in behind and down through the scene to the lower right while PDH opens the shutter and has a has a diffuse light, barely traceable, permeating the scene. A chair appears only in the De Hooch composition where x-rays revealed once sat a male figure which was then removed, leading many historians to assume that this canvas was the model for the other since PDH arrived at this composition thru his own process of elimination.

Why else would he have put that figure there in the first place? Well, PDH rarely painted solitary figures. In Peter Sutton’s catalogue raisonnè spanning 35 years of some 150 paintings, there are only 3. In fairness to Vermeer, the argument could also be made that PDH liked what Vermeer did and tried his own version with two figures and then opted to leave the figure alone.

Gemaldegalerie Berlin

National Gallery, Washington DC

We can often catalogue Vermeer’s pictures often by the way the flat white walls are chopped up and peek through his compositions. Uncharacteristically, here De Hooch shows the larger expanse of empty wall space between the two in his Woman Weighing Gold. De Hooch also rarely fades heads into pictures or maps, preferring to use his doorways as portals for his figures. But here we have each artist addressing the play of figure and rectangle differently: PDH puts his figure emerging out of the rectangle (door) as Vermeer usually does while Vermeer puts his figure inside the rectangle (religious painting) like PDH does in his doorkijkjes. Metaphorically, one figure being absorbed in another higher sphere, while the other leaving that world to Gemaldegalerie Berlin join the living and the world of gold.

To echo this idea, Vermeer’s composition supports the woman’s hand lifting upwards towards the heavenly scene in the painting reinforced by the black vertical of the picture frame, while PDH’s motif remains in this world and pulls the hand downwards towards the gold in the scale that resonates throughout the whole scene, supporting the more worldly motif, via the chair vertical.

Could this incredible matchup of masterworks in similar size have been commissioned by a single client, choosing the master duelers of Delft to attack this motif: Vermeer with his characteristic religious bent and De Hooch with his more humanist approach?

Un-Vermeering

The new discovery of the Cupid picture hidden behind the surface in the Dresden Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window” shows us clearly how the present tastes can change the past. Someone apparently post Vermeered that picture by emphasizing the solitary single figure and painting out the Cupid picture.

This newly uncovered painting within a painting also appears in the much later National Gallery picture and should now bump forward the previously dated circa 1657-8 Dresden picture. To be sure, the dating on many Vermeer’s works is highly debatable but it should be noted that a repetition of objects in Dutch painting often implies a closer chronology.

But comparisons with De Hooch’s work can sometimes be helpful with dating. This new Vermeer composition relates to De Hooch’s pictorial interests in the mid 1660’s where curtain, painting and interior geometry create a dense overlapping of forms and movement. And even whether the artists were in touch or not, there is a general human climate that affects the tone of artist’s works throughout history, discernable even decade by decade. Hence our ability to look at a pictures and detect the specific time and place they were created. We feel the changes and evolution of human culture and its expression thru the artists work of their times.

National Gallery, London

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

Rather than a cut out figure against a white wall, Girl Reading a Letter is now a complex dynamic of geometry and figure. There is a drapery within drapery dialogue: the green foreground fabric sets the boundary of the painting and our world, while the red drape hanging from the window swoops into the scene from the top left and journeys thru the glass, wall, head and Cupid painting to the right middle edge of the picture. This movement is synchronized in parallel with a movement beginning at the lower window and continuing through chair, rug, and still life and ends at the bottom right of the canvas.

Perhaps more pictures and maps will be uncovered in Vermeer’s work and thus, “De Hoochifying” his ouevre more. The few remaining empty background pictures in X-rays show traces of maps that may or may not have been overpainted by Vermeer. Regardless of whether we add these new pictures to this camp, it is clear Johannes constructed his pictures with the dynamic juxtaposition of figure and rectangle, of picture in picture as Pieter de Hooch began doing in 1656.

Gemaldegalerie Berlin

Rijksmuseum

The Love Letter and Woman Feeding the Parrot

The Letter and Woman feeding a Parrot seem at first glance unrelated PDH/Vermeer motifs. Vermeer in his later period returned to multiple figure compositions as PDH had done all his life; his interiors now contained a relationship contained within the rectangle rather than our relationship to his solitary figures. Here we have the mistress, who has paused from playing the lute, holding a freshly handed sealed letter looking quizzically at her maid, who looks back smilingly. In the Pieter de Hooch, we have a gentleman holding the door of the parrot cage open so the lovely young woman can amuse herself with the parrot while holding a drink. On closer look, however, it is likely that both scenes are about the same thing: seduction, one via a letter and one by a parrot. Both letter and parrot are indirect means to attract the women.

Rijksmuseum

Wallraf–Richartz Museum

The woman in the Vermeer is holding a cittern, a type of lute used at that time as a symbol of love(often carnal). This is further reinforced by the removed shoes at the bottom of the scene, also a reference to undressing and sex.

Both visually of course are pendants and likely refer to the earlier composition by Samuel Van Hoogstraten, the eminent painter and writer, also with two sandals at the bottom of the scene, suggesting what might be happening around the corner. All 3 pictures have a propped broom at the side, suggesting that daily tasks have been postponed for an amorous interlude.

Van Hoogstraten was a bit of a Northern Renaissance man, admired by fellow artists for his art, writing and perspective box constructions. He was an accomplished portraitist, genre and trompe l’oeil painter. He expounded eloquently about the new purpose of painting in this new age of the “seen,” in his Introduction to the Academy of Painting, or the Visible World.* The new purpose of art, he wrote, is to show the natural world. He was interested in tricking the eye via curtains , shadows, trompe l’oeil and his “peep show” boxes. The Slippers in the Louvre is dated to the early to mid 1660s and expressed his naturalistic views of art as much as a construction of rectangles within rectangles which must have attracted Vermeer and PDH.

Louvre

Louvre National Gallery, London

Vermeer, however, replicated more elements of the Van Hoogstraten, slippers, paintings, fabrics, tile pattern and painting style and the De Hooch, while more closely duplicating the Vermeer composition, is one step further away from the Van Hoogstraten.

Although of different sizes, both Vermeer and the De Hooch side by side look like pendants. Both show half-draped curtains in the trompe l’oeil style leading us into the scene, with assorted items in the foreground, leaning broomsticks, the figures and then a glimpse into a farther room. While Vermeer always avoids taking us too far back and flattens things out, PDH lets us wander into a distant space. Although the PDH once bore a date 1668, the clothing and style point to the later 1670s. There are also similarities with the model, dress and rug of the 1677 London work which implies it postdates Vermeer’s version.

I tried understanding the relationship between these pair of pictures backwards. Since Vermeer died in 1675 and PDH often depicted life events in his work, I expected to find some painted reference in the work of his close friendly rival. I looked this scene again, the last referential picture they did “together” and noticed a white jug unusually placed on the floor of the PDH. It is, in fact, a slight variation of the jug Vermeer made famous now in several of his pictures including the Music Lesson. Was this his last tribute to his friend? This jug very rarely appears in other pictures by PDH.

*original title: 'Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst: anders de zichtbaere werelt', published in Rotterdam, 1678

Almst all of Vermeer’s pictures expound upon the lateral voyage of light across the picture plane from left to right. Whether it is the daylight caressing the Girl with the Pearl Earring or the sliver of window light traveling from upper left to the lower right corner of most of his interiors, the light of his pictures moves laterally to us. This light is counter balanced by the dark flat maps and paintings that reinforce the 2 dimensional design. The basic structure of his work is flattened darks upon a side-lit plane.

De Hooch on the other hand uses his contre-jour light openings and doorkijkjes against a more flattened dark plane. Here the light travels to us perpendicularly as geometric cavities of light on a dark surface. The picture plane folds in on itself in successive planes of light and dark that echo his doorkijkjes.

Overlaying the general light on dark structure, De Hooch employed a full range of tone, color and illumination effects, chronicling the many behaviors of light. Vermeer confined his pictorial vocabulary to a fewer elements but refined them carefully. In his later work, Johannes discarded painting the light source entirely and worked with subtleties within an even more limited range of darker tones which then, faded into blackness. Perhaps the difficulties in his life and in Holland in the early 1670s, contributed to this darker vision. We do know by his wife’s account that his financial ruin weighed so heavily upon his that, “...as a result and owing to the great burden of his children, having no means of his own, he had lapsed into such decay and decadence, which he had so taken to heart that, as if he had fallen into a frenzy, in a day or day and a half had gone from being healthy to being dead.” Vermeer died at just 43 years old in 1675

Ironically, De Hooch was also considered to have suffered an untimely tragic end when most historians assumed he had died in an Amsterdam insane asylum in 1684. However, it was later discovered in a document unearthed by Franz Grijzenhout,* that it was in fact kk his son, Pieter, who had perished. After being named as parents during the transfer of their son to that institution Pieter de Hooch and his wife vanished. There are several canvases dated 1684(and even one 1686, discovered by the author) but where they were painted and the date of the artist’s death remains a mystery. The fact that records mention the asylum burying the De Hooch’s first born alone is also perplexing.* *

Did Pieter and Jannetje move to a far away city, sail to the West Indies…or even go to America? Due to Holland’s economic woes in the 1670’s, many Dutch left the country to pursue opportunities in new lands.

The National Gallery Washington

National Gallery, London

Metropolitan Museum of Art

* New information on Pieter de Hooch and the Amsterdam Lunatic Asylum , Burlington Magazine 2007

**SAA, Gasthuizen (‘Hospitals’), inv. no.951, Krankzinnigenboek (‘Book of the insane’), 1640–1745: On 22nd March 1684 Pieter Pieterse de Hoogh died and he was buried on behalf of this house in St. Anthony’s Cemetery.

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting, National Gallery of Art, Washington Photo Courtesy of the Author

There are other works to explore these two artists’ connection within this special golden sliver of art history. The National Gallery of Art exhibit in 2017 Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry curated by Arthur Wheelock, was a special opportunity to do so. Upon the news of the exhibit, I immediately bolted to Washington and gasped at the 70 works of artists like Van Mieres, Ter Borch, Metsu, Steen and Dou that were spectacularly curated and all part of this milieu. But nothing was as thrilling as the final room of the exhibit where I stood open mouthed in front of the 2 pairs of Vermeers and De Hoochs that were brought together. The Love Letter, Woman Feeding the Parrot, and the two Women with Balances were hung together for the first time and as concluding testament to their unique connection and influence in Dutch genre painting. The Balance pictures that were set next to each on the final wall of the exhibit were transfixing. The incredible dialogue between these two pictures embodied the mystery and connection between these two great artists. I stood for hours and looked and looked, and then closed my eyes, trying to go back to the mid 1660s and imagine where each of these canvases were and what these two artists were thinking when they painted them. Perhaps they were last seen side by side in Delft or Amsterdam? There was a great secret between them to uncover.

But no force of will or desire I had could break thru these doorkijkjes into the past. These pictures were now trapped in our time. I left the show satisfied but defeated. The mystery of Vermeer and De Hooch remains alive and well, still leaving us much to uncode within these enigmatic rectangles.

Allen Hirsch is a painter, writer and entrepreneur. He collects 17th Century Dutch art and is currently working on an art historical memoir of Pieter de Hooch.

Join our mailing list to receive curated updates, special features, and invitations to events that define the world of the discerning few.

Sign up today and never miss what’s next.